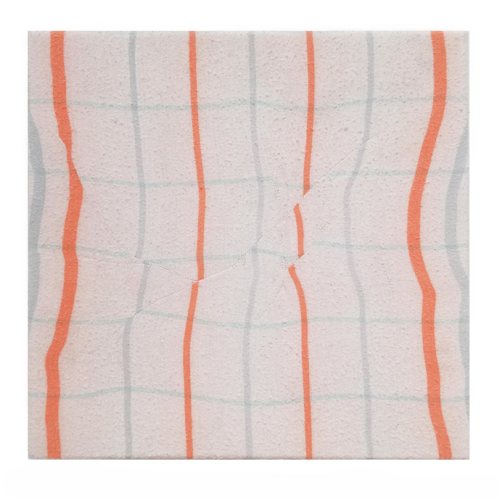

stitched paintings

represented by the HIDDE VAN SEGGELEN, Hamburg

“There is a nakedness about this art, something is exposed to the bone/grain. Should we call these works paintings? Their sensations of animated form may suggest otherwise… Before our eyes we see fabrics (a product of craft and spirit) undergo infinitesimal mutations. Ellemers’ art touches the point where material becomes spirit.”

Mark Kremer | curator writer

films and television

produced by Stichting Benina

"Like her paintings, the film is a sequence of an endless, varied repetition of actions and movements. In the sparsely lit factory, the semi-transparent enormous blocks of ice light up as they glide through the frame, being stacked, pushed through, loaded, transported and unloaded. The process is of a frightening beauty, a merciless naturalness and a wondrous ordinariness that few know about. The film is not a story, not fiction, not a documentary, not an image report, not journalistic or contemplative, but a painterly imagination that takes hold cinematically. In this sense, 'Es Balok' is no different from her non-painted canvases. None of those are what you attribute to a painting either, and yet they are pictorial.”

Alex de Vries | curator writer (following preview film 'Es balok')